2020 was a dreadful year for pretty much everyone everywhere.

I reckon my 2020 was no more nor less dreadful than the average person’s in the scheme of things.

But I’m not sure many people had a more eventful year than I did.

Let’s just take the month of March at the very start of the pandemic when my journal looked something like this:

Catch Covid.

Give it to my girlfriend of six weeks.

Move from London to Essex to nurse her.

Run a household comprising a recovering mother and two teenage children that I had met once and then only briefly.

Stay there with them when the first UK lockdown is declared.

Lose my job.

The end of 2020 was no less eventful:

My girlfriend (now partner) has a heart attack

Another lockdown is declared

She is kept in Harlow hospital over Christmas and New Year dodging Covid as it sweeps through the wards

She has open heart surgery and a double by-pass operation

But there was an up-side.

Learning to be a bad birdwatcher

The house where we locked down resembled a menagerie at times with assorted young people, their boyfriends/girlfriends and a cat, all tripping over each other.

The pressure to max out on our one hour a day of permitted exercise was high, understandably. There were woods at the end of the cul-de-sac so the pair of us were out every lunchtime to try and retain our sanity.

I was curious enough about the birdsong we heard in the hedgerows that spring to order Simon Barnes’s aptly named ‘A Bad Birdwatcher’s Companion’.

His readable no-nonsense chapters on the 50 most obvious species in the British Isles was pitched at just the right level for us.

Thanks to Simon I learnt the difference between a house sparrow and a dunnock, ‘perhaps the most overlooked bird in Britain’ according to him.

I also realised that the birds that roosted on the roof of the house that awoke us each morning with an infinite variety of squeaks, buzzes and clicks were those arch mimics, the starlings.

And I came to love, and I mean really love, those masters of the skies, the swifts that appeared out of nowhere for three short months of the summer and screamed down the road in close formation.

The revelation that was rewilding

Our appetite duly whetted, once we were allowed to go further afield we took trips to the nearby Essex coast.

The word ‘wilderness’ used to conjure up images of the Peak District or Yorkshire Moors, bare windswept landscapes peopled by characters from the novels of the Brontë sisters or of Thomas Hardy.

However when we discovered the Essex marshes I had never seen anything like it for real desolation. I just loved it.

Our first visit was to Wallasea an island that was originally farmland, but was later abandoned.

Now a nature reserve run by the RSPB, it was re-sculpted with three million tonnes of clay dug out of the bowels of inner London to make way for what became the tunnels of the Elizabeth Line.

Natural creeks and salt marshes had formed that proved attractive to migrant wading birds and once rare species like Marsh Harriers and Short Eared Owls.

I learned loads at Wallasea, not just about which birds were which but also how landscapes can shift and re-form.

After the initial human interventions of the lorry loads of London soil and a breaching of the sea walls to let the water in, nature was pretty much left to its own devices. And the results were stunning.

Again, I was surprised to learn that what we’ve grown up to think of as ‘waste land’ can be in fact extraordinarily productive for biodiversity.

Ode to the Essex nightingale

We visited nearly all the reserves along the coast that year.

Another destination that was just as gloriously desolate was Fingringhoe Wick just up the coast near Colchester.

In the first half of the 20th century sand and gravel had been extracted there to build a growing London. So it was a barren lunar landscape when the Essex Wildlife Trust took it over in 1961. But they largely let nature decide what happened next.

It is now one of the finest nature reserves in the country that plays host to up to 200 species of bird and over 50 types of dragonfly and butterfly.

It was at Fingringhoe that I heard my first nightingales and turtle doves, both rare and endangered in this country. There was something about this scrubby rewilded Essex landscape that they liked enough to return to from Africa year after year.

Of course, they may have been a common sight and sound of my childhood but I was not switched on to nature then. So my baseline as to what is normal was not set in the 60s and 70s. It started ticking in 2020 so I did not know what I was missing.

The only flyway is Essex

Then imagine my surprise and delight when I read in 2023 that the UK had applied to UNESCO for World Heritage status to that whole coastline, now called the East Atlantic Flyway.

It was like a 12 lane motorway for migratory birds to get to and from their breeding grounds, for some species from one end of the globe to the other.

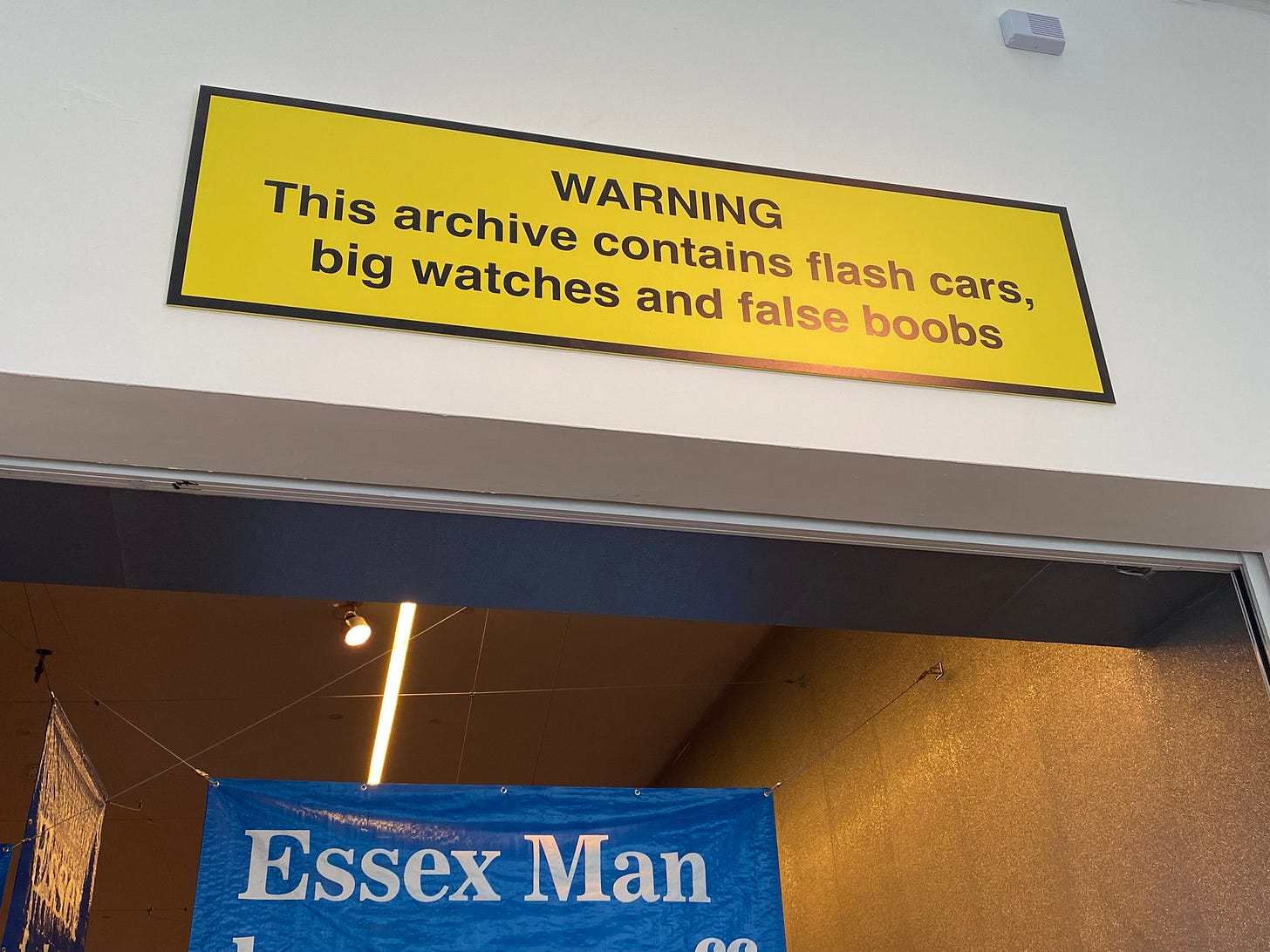

But it really wasn’t the image of Essex that I had previously had in my head before moving there in the Pandemic.

Since the 80s the chattering classes in London had lapped up media creations like ‘Essex man’ and ‘Essex girl’. Othering a whole county as vulgar and greedy later went national with ‘The Only Way is Essex’, a TV reality show showcasing the exuberant behaviour of young people that was in fact far from unique to this corner of eastern England.

As I became an Essex man myself over the course of the Pandemic, I realised how patronising these stereotypes were. I am now a fierce defender of that county and all who sail in her.

We eventually left Essex in 2023, having disposed of the house, the children and the cat, to step into the London chapter of our re-wilding adventure.

But I have never forgotten how my perceptions of Essex, its people and its landscapes had changed in such a short period of time.

Only now that I am writing this do I realise how life-changing those three years had proved to be.

Oh my goodness Mark! What a rollercoaster it has been since I last saw you. I’m so sorry about your parents. I lost my dad in 2022 so I know something of what you’ve been through. I’m excited to read about your adventures - it seems we’ve both discovered nature in the midst of all that trauma.